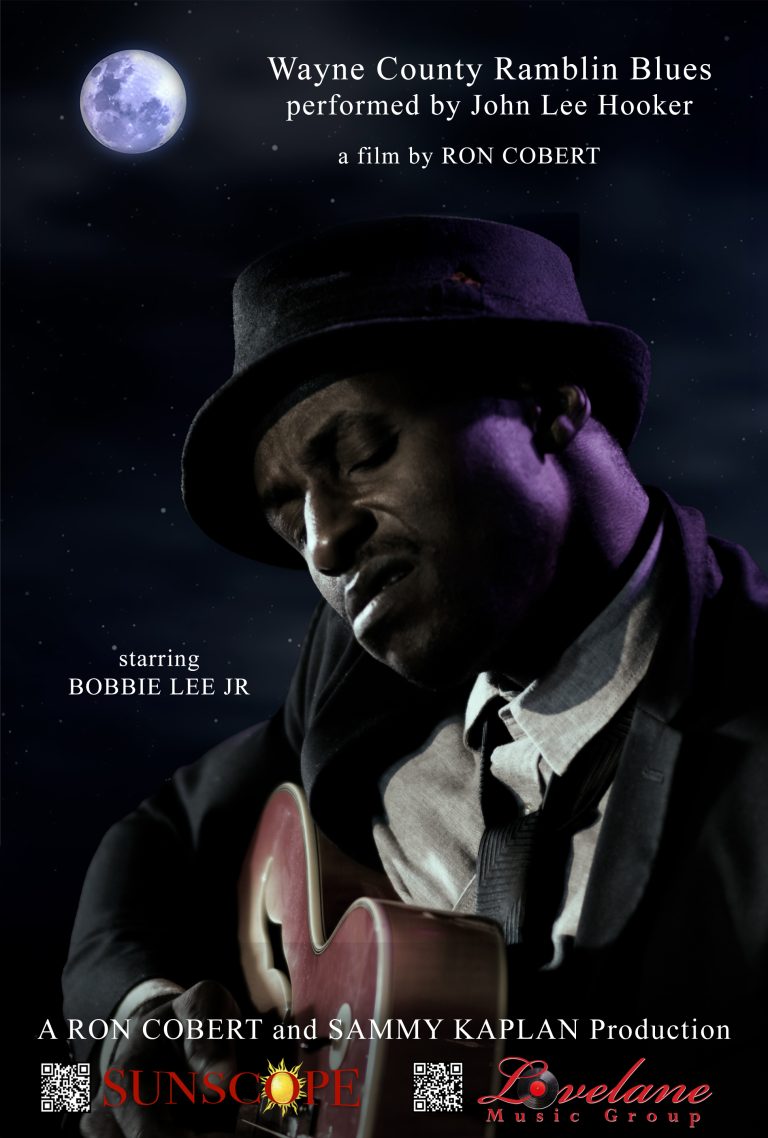

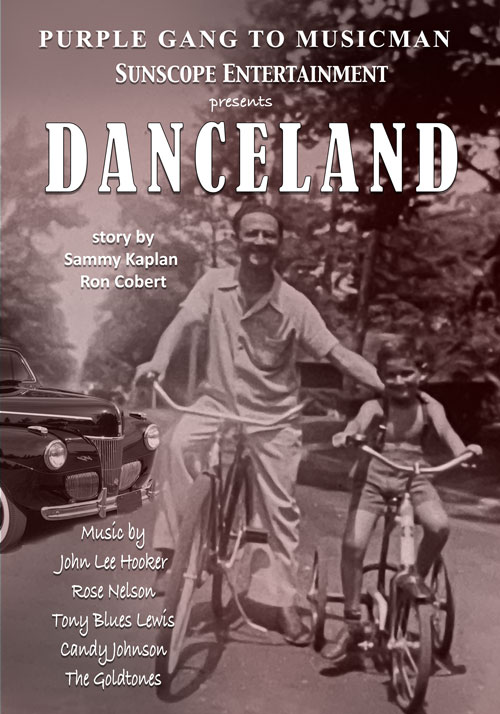

Story by

Sammy Kaplan and Ron Cobert

Logline:

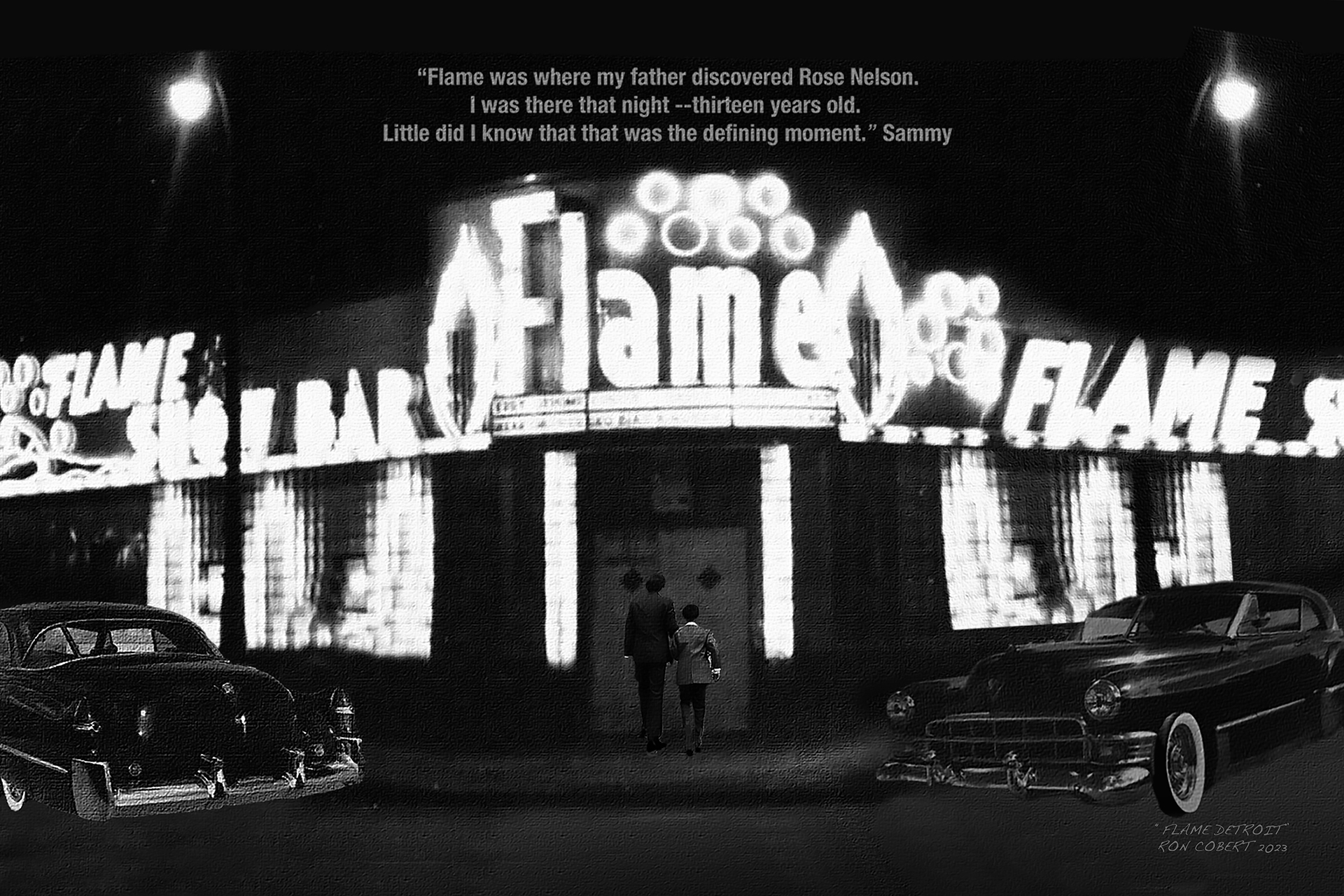

Danceland is based on an authentic American music-bio-drama that delves into the profound journey of a talented music man torn between the clutches of the notorious Purple Gang and the pursuit of his true passion, listening to music. Set against the backdrop of prohibition-era Detroit, this compelling tale explores the transformative power of music as our protagonist must navigate dangerous alliances, personal sacrifices, and forbidden friendships. It’s about breaking free from the grips of crime to carve a path toward the budding music industry, 1948, Detroit, Michigan.

The DANCELAND: THE PATH TO A MUSICMAN Film is all about the Lovelane Music music, specifically the Danceland Years Album:

To Listen, CLICK HERE

- What’s the Matter with World – The Goldtones

- Wayne County Ramblin’ Blues – John Lee Hooker

- Six O’ Nine Boogie Take One – John Lee Hooker

- Cotton Pickin’ Boogie – John Lee Hooker

- 1949 Grievin’ Blues – John Lee Hooker

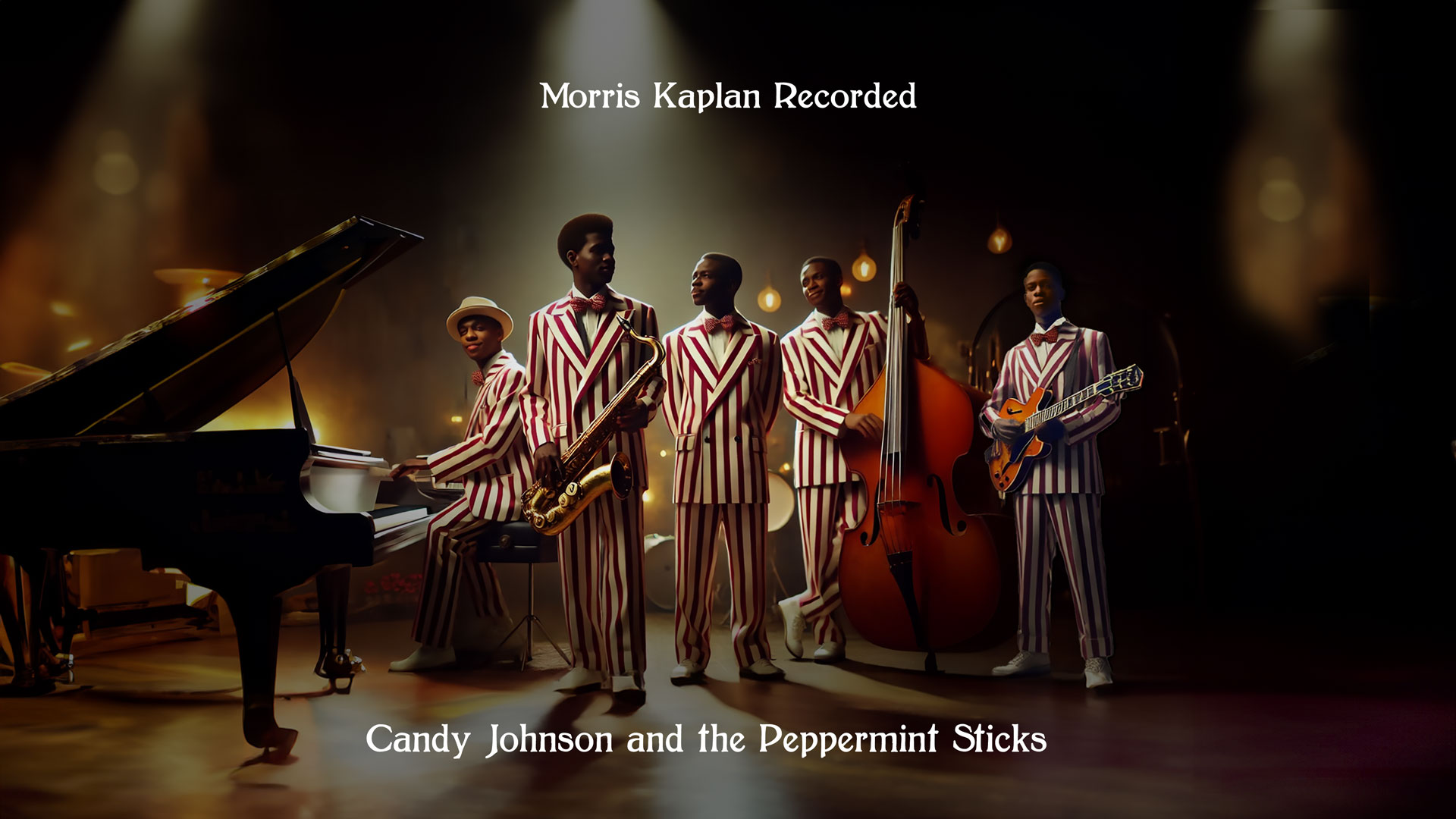

- Ebony Jump – Candy Johnson

- Robin’s Horn – Candy Johnson

- Southside Saturday Night – Candy Johnson

- Daybreak Blues – Candy Johnson

- Sunset Jump – Candy Johnson

- Stampin’ – Candy Johnson

- Lonely Girl – Rose Nelson

- Take Me Back Daddy – Rose Nelson

- Lord Have Mercy – Tony Blues Lewis

- Gonna Call on You Babe – Tony Blues Lewis

- I’m Gonna Catch Me a Freight Train – Tony Blues Lewis

- Gonna Buy Me a Shotgun – Tony Blues Lewis

- Lazy Daisy – The Goldtones

Beginning the Story